Kyrgyzstan: anti-extremist legislation is considered repressive

The authors of the report “Anti-extremist politics in Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Comparative review” recognized the anti-extremist legislation of Kyrgyzstan as repressive. Human rights activists believe that it contains repressive potential, which is also used as a tool for personal and political reprisals against opponents.

The Kyrgyz anti-extremist legislation includes the law No. 1501 “On counteracting extremist activity” dated August 17, 2005, the Criminal Code provisions related to the law, as well as corresponding provisions of other regulatory acts. This law is mainly borrowed from a similar Russian Federal law.

One of the weak point of this document is the too wide conception of extremism, which includes both terrorist activities and, for example, publishing pictures with symbols and attributes of extremist organizations on social networks or storing leaflets and books that are listed on extremist materials.

“The vague wording in the definition leads to the fact that law enforcement authorities and judicial experts, assessing the so-called extremist material, are guided by their personal beliefs and concepts,” the authors of the report note.

Human rights activists note that the concept of “religious extremism” is also not given a clear interpretation in any of the normative legal acts of the Republic.

The authors of the review believe that in this regard, the concept of religious extremism can be interpreted quite broadly, speculatively and not correspond to the spirit of anti-extremist legislation, and the decisions made by the courts may not fully take into account the objectively existing difficulties in analyzing certain materials, works and publications about creed for signs of extremism.

Anti-extremist law enforcement in the Republic concentrates mainly around the activities of organizations. Currently, the courts of the Kyrgyz Republic recognized 21 organizations as terrorist or extremist. Most of them are religious, mainly Islamic, movements and groups of various degrees of radicalism.

The legislation of the Kyrgyz Republic refers to extremist materials “official materials of banned extremist organizations”, materials with signs of extremism, the authors of which were convicted in accordance with international legal acts for crimes against peace and humanity, as well as any other, including anonymous, materials with signs of extremism.

At the same time, the document says that the materials can be recognized as extremist only by the court on the recommendation of the prosecutor, at the place of their discovery, distribution or location of the organization that produced these materials.

A copy of the court decision that has entered into legal force on the recognition of information materials as extremist is sent to the Ministry of Justice. The list of extremist materials is subject to periodic publication in the media, as well as on the official websites of authorized state bodies in the field of justice that counteract extremist activities.

“However, in the practice of courts reviewing criminal cases on the storage, distribution of extremist materials (see below the Criminal Code norm), the presence or absence of material in the list of extremist usually does not play any role. The prosecution does not present the relevant decision on recognition by the court of the alleged material as extremist, and the courts considering criminal cases do not pay attention to this circumstance,” human rights activists say.

The Law “On counteracting extremist activity” prohibits the use of public communication networks for carrying out extremist activities. However, the legislation does not contain special norms about the mechanisms for blocking materials on the Internet, as well as the registry of prohibited network materials is not maintained in the Kyrgyz Republic.

“However, with the implementation of court decisions on blocking certain sites, the authorities of the Republic do not have problems. As a result of the interaction of authorized bodies with providers, the latter stop accessing both little-known sites and large portals that are on the list of extremist materials. Thus, the entire Internet Archive (archive.org) was blocked for posting some Islamist materials, and the website of the famous Ferghana news agency (fergananews.com) was blocked for publishing an article about xenophobic comments about Uzbeks on social networks, since the article was recognized as extremist,” the authors of the report write.

In addition, according to researchers, recently individual pages on popular social networks are often recognized as extremist.

For the first time, there was a question in 2018, when 19 Twitter accounts were recognized as extremist. Then the State Committee for Information Technologies and Communications of the Kyrgyz Republic announced that it would not block the entire social network (blocking individual accounts is technically impossible), but would begin to interact with its administration on the issue of blocking accounts. Whether the authorities of the Republic established contact with popular social networks was not specified. One way or another, the practice of banning materials on social networks is only expanding: 19 decisions mentioned above for 2019 were concerned blocking 64 sites and 233 accounts on social networks and channels on video hosting sites.

The authors of the review also consider the norms of the Criminal Code, that entered into force in January 2019, as imperfect.

Although the article 313 of the Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic criminalizes acts related to inciting various kinds of hostility, most of the criminal cases are connected with “religious extremism”. Moreover, the basis of the accusation in such cases is usually the conclusion of a religious expert examination.

As an example, they cite the process of the imam of As-Sarakhsiy mosque in Kara-Suu city, Rashod Kamalov, widely discussed on social networks.

The imam was convicted of inciting religious strife, and as the head of the cell of the banned organization “Hizb ut-Tahrir”. The court of first instance sentenced him to five years in prison, the appeal court tightened the sentence to 10 years. The charge was built around three copies of the same video of the Friday sermon with a discourse on the meaning of the concept of “caliphate” in Islam. Kamalov claimed that he had no intention of inciting hate and strife. However, the court agreed with the investigation, which substantiated the accusation with the conclusion of a religious expert examination, in which it was noted that the investigated material contains calls for a change in the constitutional system.

Part 1 of article 314 of the Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic gives qualifications to acts related to the creation or leadership of an extremist organization.

“According to the note to this article, a person, who voluntarily ceases to participate in the activities of an extremist organization, is exempted from criminal liability if the person assisted law enforcement agencies in identifying and prosecuting the organizers of such kind of organization. However, clear criteria for such “assistance” are not defined, which leads to an arbitrary interpretation of this norm by investigators and courts,” human rights activists write.

In practice, people are often held accountable in connection with the participation in the activities of such banned organizations as Hizb ut-Tahrir or Yakyn Inkar movement. As a rule, confessions of the accused people are presented as justification for the prosecution in such cases. For example, in cases of the activities of the extremist religious organization “Hizb ut-Tahrir”. In cases involving participation in the activities of Yakyn Inkar, the investigation may provide evidence that the accused carried out davaat without permission, refused vaccinations, dressed in Arabic clothes, and grew a beard.

According to part 1 of article 315 of the Criminal Code of the Kyrgyz Republic, it is forbidden making, distribution, transportation or transfer of extremist materials or their purchase or storage for the purpose of distribution, use of symbols or attributes of extremist organizations, including on the Internet. This norm of the Criminal Code provoked reasonable indignation of human rights defenders and lawyers, as it allowed prosecuting for storage of extremist material or symbols. Evidence of the criminal intent of their storage to hold accountable was not required.

“It should be noted that no post-Soviet state, except the Kyrgyz Republic, has criminal liability for such an act as the storage of extremist materials. Usually there is an administrative responsibility for this. In the criminal process, the fact of storage of prohibited materials can only be one of evidence of another act of extremist orientation. The use of prohibited symbols does not even entail administrative responsibility in all countries,” the authors of the report note.

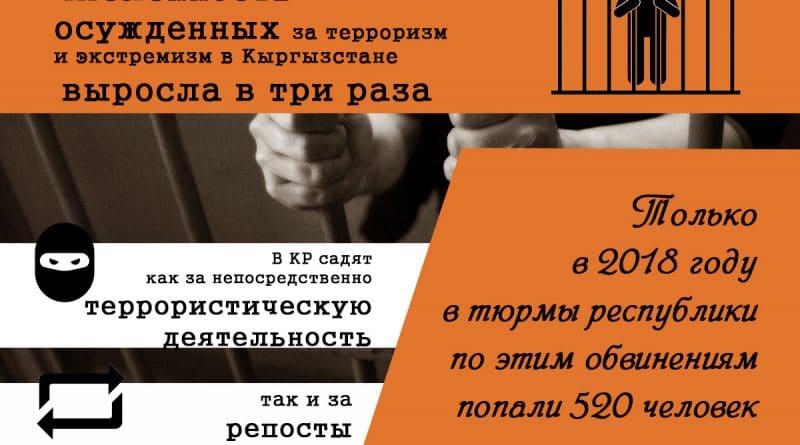

Meanwhile, the number of people accused of storing extremist materials, especially on social networks, in the Kyrgyz Republic has increased in recent years. If in 2014, according to official data, there were only 24 persons, who “committed a crime” stipulated by article 299-2 of the then-revised Criminal Code, then in 2015 there were 46, in 2016 – 89, in 2017 – 95, and in 2018 – already 181. Their share in the total number of people accused of committing crimes against the foundations of the constitutional system and state security amounted to 61%. Similarly, the number of recorded crimes under the article increased.

At the same time, from 2016 to 2018, conditional terms were not assigned under this article. On December 18, 2019, the Department for Combating Extremism and Illegal Migration under the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic reported that since the beginning of the year, more than 300 people have been detained for distributing extremist materials. Most cases of prosecution for the storage of extremist materials are related to Hizb ut-Tahrir materials. At the same time, according to the data provided by the Supreme Court of the Kyrgyz Republic in 2016, ethnic Uzbeks made up more than half of those convicted of terrorist or extremist crimes.