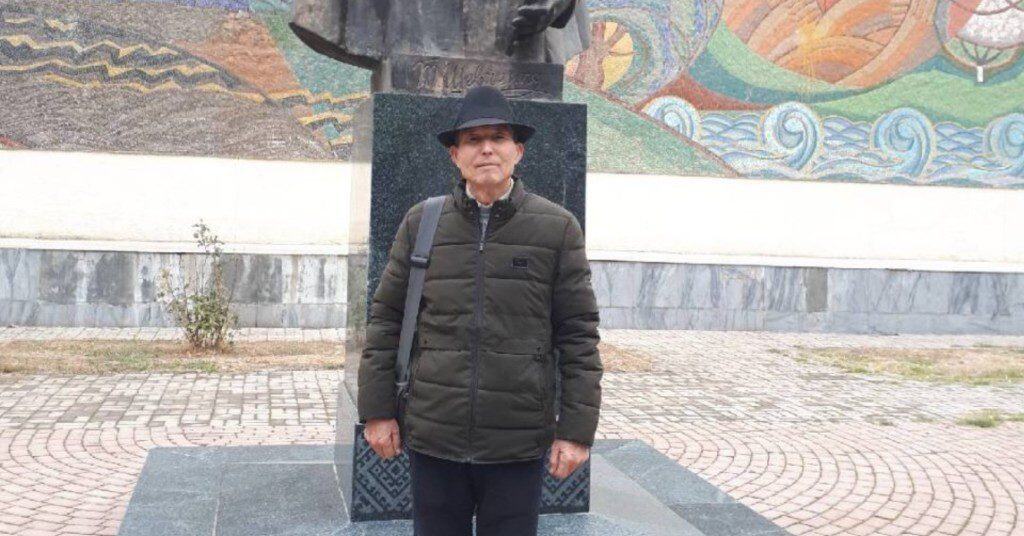

ACCA publishes the story of a political prisoner, about how the authorities decided to release him, but canceled the decision due to the fact that the human rights activist did not confess to the President of the country to camera. Here is the story of Salidjon Abdurakhmanov, a native of Karakalpakstan.

“Thousands of prisoners, who are unjustly convicted, are languishing in prisons and colonies of Uzbekistan. Even after their release, they cannot rely on rehabilitation, and one exception only confirms this rule.

In 2008, I was sentenced to ten years in prison. Colleagues and the international community immediately recognized the imputation as trumped-up; it was possession of drugs on an especially large scale for the purpose of sale. I had to serve nine years and four months, was released on October 4, 2017. I talk about four days with a premonition of imminent freedom, when I managed to serve six years. The villains fooled me, but did not break me …

… March 14, 2014 was no different from ordinary day. I took a morning dose of medicines. I had been undergoing treatment for half a month in Tashkent, at the Central Hospital of the Main Directorate for the Execution of Punishment.

Closer to dinner, they called me to the doctor. Eight people were sitting in the office. It turns out that it was a medical board, they were interested in my health. Having learned that it was tolerable, they said that they were giving a conclusion for parole.

I felt a great spiritual uplift. Finally, the day has come, which every convict is waiting for! If I spent almost six years behind bars, then this excitement, I think, is akin to the feelings of a soldier who went through the war and heard the news of the end of all this horror.

On leaving the office, they photographed me, and after dinner they invited to the court. The hearing of the Khamzinsky District Criminal court was held on the territory of the fire department. Three people were sitting against the wall. They were the judge, the prosecutor, and another one. There were 7 of us, including three on a stretcher.

When it was my turn, the judge, a young man of about thirty-five years old, after a few usual questions to me and those sitting next to me, announced early release on parole.

I thanked him and went out. In the ward of the therapeutic department everyone congratulated me.

It was 15, then March 16. Silence. No one invited anywhere. There was no particular depression. I read some book, played checkers.

On March 17, after lunch, I was summoned to headquarters. They gave me to change into civilian uniform, issued a medical report. At the first passage, near the slatted reinforcing door, the assistant to the head of the colony (the hospital, Sangorod in public, is part of the colony No.18 which is located here) hands in a certificate-decision of the court on parole.

There was some room in front of the last gate. Here they issued money for the road. They gave a police officer accompanying me to my house. It turns out that this is determined by the instructions on the procedure for the release of convicts of retirement age directly from Sangorod.

They invited me to the video camera. It is an established procedure relating to prisoners with “tachkovka”, that is, unreliable. According to this unspoken rule, a prematurely released person must speak to the camera that he has revised his views on the facts of his crime in the prison. Well, he made the corresponding conclusions, of course, thanks to the “educational activities” held in the colony. At the same time, there must certainly be words asking for sincere forgiveness addressed personally to the President of Uzbekistan Islam Karimov.

Those released with “tachkovka” are prepared for the video camera, but they made an exception for me. One of the officials of Sangorod first talked with me. To his credit, he did not say about the need for what and how to say it, he only noticed that I know well what to say.

When they filmed, there were six officers in the room. I said on record that upon going out to freedom I would do family and house affairs, bring up grandchildren, etc. There were no familiar words of repentance and forgiveness for the president, and there was no guilty plea, since they threw drugs into my car.

I did not have to wait long. After 7-8 minutes, the video camera operator said that there were technical problems and we needed to do it again.

They filmed. My words were almost the same, with some permutations. I want to note that there were three officers near the computer. So, they filmed and sent it somewhere.

After some time, it turned out that again there were some “problems” with the equipment. It was repeated.

So, I already knew for sure that I had not complied with the requirement of “repent”. Someone from the higher authority was deciding my fate.

Then I asked the officer for permission to call my son on his Tashkent’s number. The phone was located two meters behind the barrier. The granddaughter’s voice was clearly audible; she asked her mother for the phone, but her voice abruptly interrupted, as the officer quickly hung up.

I didn’t ask about anything. Everything was clear to me already, torture continued and there would be no limit to humiliation. To preserve his miserable existence, exorbitant conceit and greatness of his modest position, this official (I don’t call him a person) was ready to crush simple human dignity, elementary decency. Didn’t they understand that it was not me who was humiliating, but they?

The fourth shooting ended with my words that, once freed, I would continue to work for the rule of law and protect human rights. A few minutes later they announced me that day it was already late, and they would release me next day.

I put money and documents on the table to one of the officers (no one asked me about this) and, escorted by security guards, left the room. The clock in the corridor of the therapeutic building showed eight p.m.

A few days later, I was transferred to the colony No.61 in my “native” Kashkadarya region. Ahead of this release, very long thousand two hundred eighty-seven days and nights awaited me.

After being released from the Khamzinsky (now Yashnabad) District Criminal court in Tashkent, I received the certificate:

“Documents on convicted Abdurakhmanov Sali Abduraimovich went to court on March 13, 2014, but were not considered by the court.”

Leave feedback about this